Cold War: 1971-1990

Memoirs of the Battalion Commander

Lt Col John W. "Jay" Braden, Jr.

Information courtesy of the Braden family at bradenclan.com

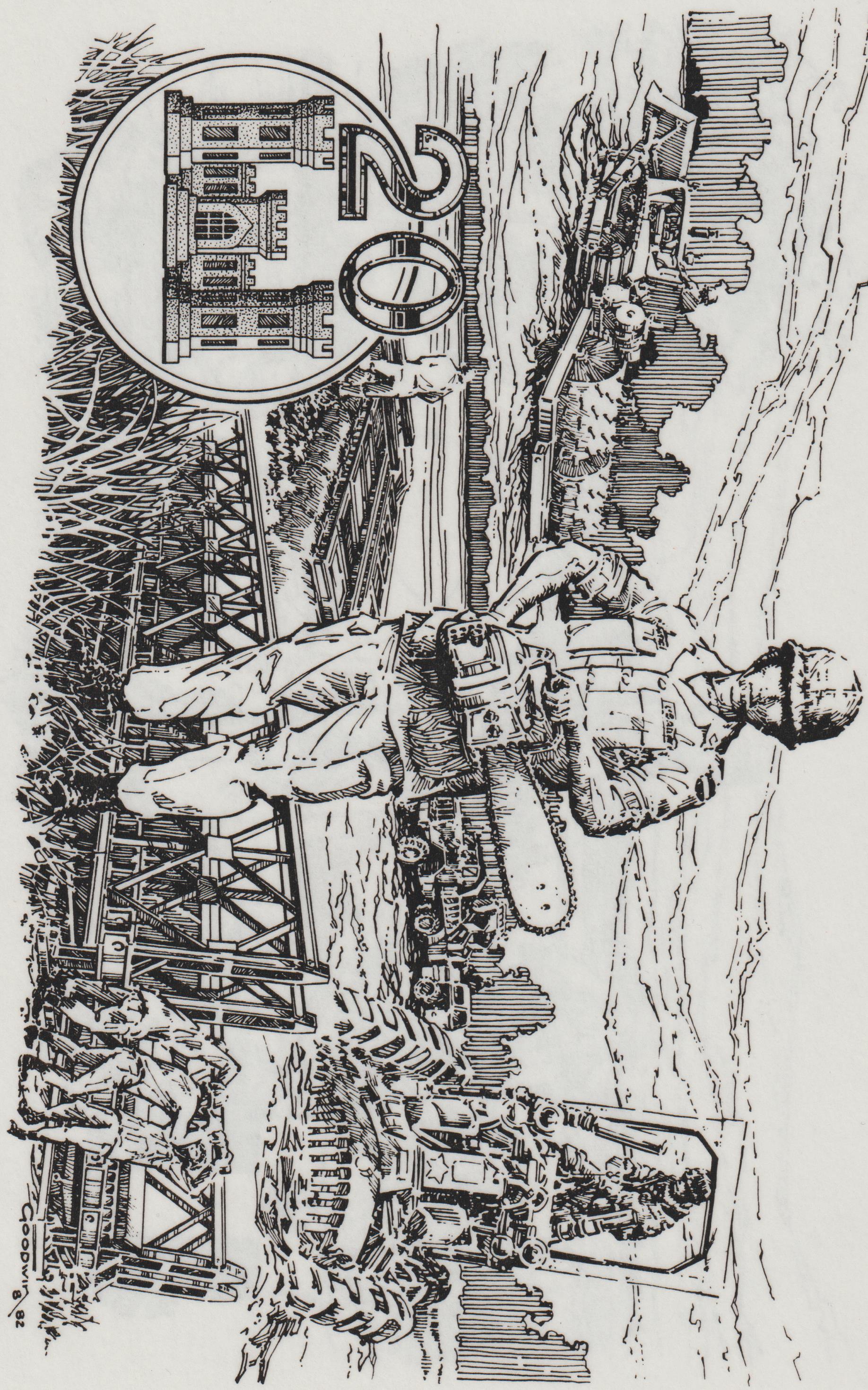

In 1981 every Army division had its organic engineer battalion consisting of a headquarters company and four "line" companies; A, B, C, and D. Most divisions had three infantry or armor brigades so there were generally habitual relationships formed as in Company A of the divisional engineer battalion would support 1st Brigade, Company B would support 2nd Brigade, etc. Company D might be used to reinforce support to one of the brigades or to provide general support to other division organizations. But it was recognized that in wartime more engineers would be required to support the division than its organic battalion, so non-divisional engineers would be brought in to assist. (The best example of this is in the artillery, where sometimes ten or more non-divisional artillery battalions would be brought in to support a division's three artillery battalions.) The 20th Engineer Battalion, with about 620 soldiers, was organized similarly to the divisional battalion, but its equipment was heavier since it was not designed to be rapidly deployed by air.

When I arrived at Fort Campbell, it appeared that the battalion was considered a post support/construction asset for the post, and it was not especially well regarded.

To turn an engineer battalion into a good combat engineer battalion requires good training programs. I was able to use my knowledge of the training ammunition system and of how to obtain training areas - both mostly a matter of being able to do some long range projections - to set up some fairly realistic and rigorous battalion training exercises, from squad evaluations to platoon evaluations. To get out of the reputation of a post support unit and into the role of a combat engineer battalion, we arranged to be part of the field training every time one of the 101st brigades took to the training area. Since each brigade of the 101st had an "habitually related" company of divisional engineers,

The divisional engineer battalion was the 326th, commanded by Ed Starbird, whom I liked - personally. Professionally was somewhat of another story. Ed tried to influence the assignment process of engineer lieutenants coming into Fort Campbell so he got the cream of the crop. Ed or his predecessors also managed to funnel most of the training ammunition allocation to the 326th, which I found out about only after protesting my "shortage" of training ammunition and engineer explosives to Forces Command, who opened their books to the Fort Campbell allocations and opened my eyes to the rip off being conducted by the 326th. We fixed that in a meeting that went to the level of the Assistant Division Commander for Support, BG Gerald H. Bethke (a great soldier).

The battalion had some challenges beyond getting past its post support label. For example, the 20th had the most AWOL soldiers for the past year (84) of any of the 29 battalion-size units on the base. At Fort Campbell with the renowned 101st, any "other" unit was subject to being considered as substandard, and this was icing on that cake. To get out of the "Most AWOLs" category, I decided to meet with new soldiers twice a week, and did so for the next three years. In the sessions, conducted in my office, soldiers learned about the battalion's lineage and honors, to include being among the first to land in Normandy on D-Day in support of the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. They also learned the consequences of AWOL, and I gave out my home phone number, with the instructions to each soldier that if you find you cannot get back from leave or otherwise be at your appointed duties to give me a call. I explained that, without a call, I would not understand at all, and as the times came for discipline under Article 15 of the UCMJ, I indicated my lack of understanding via heavy punishments in terms of loss of rank, forfeiture of pay, restriction, and extra duties. Upon my departure three years later, we had had 4 AWOLs for the year, lowest at Fort Campbell in that category. (While punishments were part of the fixing the AWOL problem, I would like to think that the battalion soldiers came to understand they were part of a highly trained unit that was respected by the division it supported.)

The 20th Engineer Battalion also had a significant maintenance challenge. The battalion had very old M51 dump trucks as its primary vehicle and they were beyond their useful life span. Finding parts to keep them running was a constant challenge. Also, in each engineer platoon there were also over 50 sets, kits, and outfits that made accountability and repair a massive headache. I also found that our annual budget (mostly used for repair parts) was in the range of $360,000.

Warrant Officer Hunley, now a CW3 and formerly of the 370th Engineer Company, was a small miracle worker in the area of maintenance. Richard ultimately retired from the Army and is now retired from being a successful general contractor doing commercial construction in the area of Clarksville. Ginger, Richard, Bonnie and I remain very close friends. The world needs more of people like the Hunleys.

One other thing I did about half way through the command was to change how the battalion returned from a local field exercise. When the exercise was over, we didn't allow any vehicle back into the motor pool except those that were already clean. Clean vehicles are a lot easier to inspect than those caked with red Kentucky mud, so this was good ... but there was a scramble to find wash points around the post. The clean vehicles admitted into the motor pool were run through an inspection line so we could begin the maintenance process for those that required parts or repairs. I just told the NCO at the gate doing the cleanliness inspections that if dirty equipment got through then he would have to clean it. Worked like a charm.

More on maintenance. How do you keep an aging fleet running, especially when the requisition priority level is low (units in Germany, for example, had higher priority for parts than we did because they were "forward deployed")? Well, part of the answer is that you try to keep a lot of spare parts on hand. But that is bad for the Army and bad for the taxpayer. But try telling that to a company commander and a motor sergeant whose careers depend on keeping a high level of operational readiness. (Operational readiness means that the vehicles are running and not down for repairs.) So as much as we tried to make the system work, we knew in our hearts that we were always carrying more parts than allowed by regulation. So what do you do when there is an upcoming IG inspection and you know you'll get written up for excess parts? One year, in preparation for the IG, we put three large containers dead center of the motor pool and told everyone that they could put their excess parts in them, no questions asked. Soon we had three 10' x 10' x 10' containers each about a foot and a half deep with excess parts. Just before the inspection, we locked all three. If the IG would have asked, "What's in those three large containers right in the middle of your motor pool?" we would have said, truthfully, that those were excess parts that we were in the process of categorizing and turning back into the system.

Still more . . .

A not-so-small note on the military’s Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), which addresses offenses that are punishable and maximum penalties for each type of offense; and it provides alternative methods to administer punishment. The system, to my knowledge, has been reviewed by numerous legal experts, and has found to be very fair. In good units, minor infractions by soldiers are handled by their sergeants, who do not use the military judicial system, but administer additional training. Additional training is supervised and the training is something that is related to soldier’s required job performance. Additional training, in itself, is not reflected on a soldier’s permanent record. Major offenses are referred to a trial by court martial. A conviction in a court martial results in a federal record for the soldier found guilty. There are three levels of court martial, depending on the severity of the offense. A General Court Martial is the highest level, and depending on the offense, can administer punishments that include dishonorable discharges, prison times, and for heinous crimes - a death sentence. There is also a level of punishment lower than a court martial that is administered by company level and field grade level commanding officers under the provisions of Article 15 of the UCMJ. Punishment under Article 15 is for relatively minor offenses, and can lead to reduction in rank, forfeiture of pay, extra duty, and restriction. A soldier who is offered the opportunity to accept an Article 15 procedure has the option to not accept that procedure but to demand a trial by court martial. Most soldiers, however, when offered an Article 15, accept that procedure, and they do have an opportunity to present matters in their defense and in extenuation and in mitigation. An Article 15 “conviction” is reflected on a soldier’s personnel file and is not helpful to the soldier when he or she is being considered for promotion and/ or retention. [As a side note, one of the brigades at Fort Campbell administered punishment by having guilty soldiers appear in full field gear: helmet, field pack, etc. but not weapons; and they were given a push mover to trim the grass in the brigade area.] With all that as a background, the question is who sits on the jury of a court martial? The answer is that a court martial board is assembled from a roster of personnel on the base that normally includes enlisted personnel of the rank sergeant major and commanders of battalions and brigades. At Fort Campbell my name soon rose to the top of the roster and I was called to serve on a board. The second time I was called was for a soldier who had stolen property in the barracks. The soldier had pleaded guilty in advance so the board had been assembled simply to learn about the case and then to prescribe an appropriate punishment. In military trials, and also in civilian trials, the prosecution and defense lawyers are given an opportunity before the procedure to question potential jury members to determine if they can, in fact, render a verdict based on the information provided in the proceedings, and not based on some prior preconceptions. This process is called voir dire (a preliminary examination of a witness or a juror by a judge or counsel of prospective jurors to determine their qualifications and suitability to serve on a jury, in order to ensure the selection of fair and impartial jury). During voir dire a lawyer for the prosecution or defense may ask a question of a specific juror or a general question to jurors and check for responses. In my case, the defense lawyer asked a general question to all jurors, and it went something like this: “Do any of you have any preconceived ideas about the soldier who has pleaded guilty to robbery?” All panel members except me shook their heads or otherwise indicated an answer of “no.” Not me. I said, “Anyone who steals should not be in the Army.” That immediately triggered a recess and I was shortly informed that thanks but my services were no longer required and I could return to my unit. As you might expect, the reply I provided during voir dire was probably circulated among the base’s defense lawyers in a nanosecond, and I was never again called to serve on a court martial panel. But this bothered me. Each battalion at Fort Campbell had a prosecution lawyer who could be called for advice, so I called the lawyer who supported the 20th Engineer Battalion and said that I didn’t make that statement to be kicked off the panel and never again invited to serve on a court martial board. He told me that defense attorneys asked a lot of leading questions like the one I had received during voir dire and a panel member should never take them too, too seriously. He said that, in the case of the question I answered, I might have considered in my mind the fact that the soldier’s father might have been a Medal of Honor winner and the soldier’s grandfather was also a Medal of Honor winner and the soldier only stole something that have been taken from him after he had exhausted all legal matters to get the item back, so it would be likely for this soldier to steal something and probably not be discharged from the Army. He said to remember his “double Medal of Honor” story when answering future voir dire questions. Interesting. And I hope this long paragraph did not put you to sleep.

One of the nice things about the battalion was its Pioneer Association, a "club" of the battalion officers that met monthly to drink a few beers and tell stories on each other. So between meetings you had to be looking for things that people did that you could use during the meeting to nominate the "victim" or that you could use to try to intimidate someone from nominating you for one or more of your mess-ups during the month, as in "Don't tell on me and I won't tell on you." It was a lot of good fun, and a battalion has enough lieutenants that make a habit of messing up so you don't get in the spotlight that many times (though I had my share of nominations). I might point out that certain embellishments were expected - and occurred - in the nominations.

The 20th had the nickname of the Wavy Arrow Battalion, and this went back to WWII when the supply people would paint wavy arrows on the battalion's supplies to make them more visible. This had evolved to the point that our road markers would have wavy arrows. And so the name of the battalion monthly newspaper. I had caught Bob Hardiman's passion for unit newspapers and we had monthly issues of the Wavy Arrow during my time in the battalion.

Robert was born while we were at Fort Campbell, at a nearby hospital in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. Not long after he was walking, Bonnie's mom Claire visited and hung a Whiffle Ball on a string so Robert could swing at it like going after a piñata. Ah, the start of an awesome baseball career.

One time we were out on a battalion evaluation. We were being evaluated by the 326th. It would be a four day exercise where they would put us through our paces, with numbers of demanding tasks and feedback on how we did them. The Army went to four day evaluations just to make sure units could work on sleep management because with shorter evaluations some soldiers could try to do the whole exercise without sleep, a safety problem if nothing else. These evaluations are serious business; the commander of the 317th Engineer Battalion, one of my earlier units, had been relieved following a poor evaluation though there were other things that had brought about this situation. Each night we would gather in a battalion staff meeting to discuss the day's operations. My Executive Officer, Major Larry McKenna, would attend the earlier briefing session at the 326th where their evaluators would report on their day's activities and the successes and failures of the units they were evaluating. Their observations would become part of the final report. He would then come back to our meeting and shared what he learned so we could learn from our mistakes and do better as the evaluation progressed. Each night Larry would return from their meeting and read off his notes: A Company didn't do the mine fields right. B Company was late in installing the bridge. C Company used the wrong procedures in filling out the target folders. D Company did a poor job with its barbed wire obstacles. Headquarters Company wasn't effective with its equipment support. Each day the tasks were different but the reports were still bad. We couldn't seem to do anything right. I was all around the battalion each day, and what I saw was pretty decent, and I couldn't be everywhere at once. My exhortations to the company commanders grew each day. "We need to be improving but we are evidently not." It got to the point at the end of day three, after another discouraging report from Larry, that I went to Ed Starbird and said I wanted to stay out a fifth day. Well, I'm sure he and his evaluation team were ready to return to garrison, but he said okay to the extension. Unfortunately, the day four evening report from Larry, though better, still had lots of negatives. I was beyond myself. The next morning I got an early visit from Ed. He had been wondering what was going on, so he sent one of his company commanders to sit in the back of our meeting the night before. It turned out that the 326th meetings included evaluator reports that fell into two categories: what we had done well during the day, and what we needed to improve upon. However, Major McKenna took no notes on the good things, and only took notes on the bad things. Apparently, though like any unit there were things we needed to work on, overall we were doing very well and had received a number of kudos from the evaluators for our efforts. Larry was there listening to Ed and when I turned to him he smiled slightly and said, "Sir, you don't pay me to pass on the good news."

I had grown to like volleyball, and we played it as a battalion-level intramural sport. We even joined a city league in downtown Clarksville to improve our skills. But we were really missing that one good player to bring us to our best. One day I noticed that the battalion had just been assigned a staff sergeant with a last name that appeared to be Samoan. I looked him up and asked if he played volleyball. His response was something like that he ate and breathed volleyball, and he was absolutely great. Yes, we won the post championship.

The battalion had a ladies softball team. Since a combat engineer battalion has no females assigned, the team came from wives and lady friends. Bonnie was the pitcher, and earned a record one day for walking 34 batters. Yes, she was in tears and it was a pretty sensitave subject so we didn't talk about it too much.

The battalion also had a co-ed soccer team that played in the city league. Bonnie and I played. In our first season it took three games before we scored our first goal, and we didn't win our first game until the second season that we played. We played on Sunday afternoon and it always seemed to rain then. We would return to our quarters a muddy mess, often sore and bruised, but we liked it.

Bonnie, was Bonnie. When new lieutenant's wives checked into the battalion, of course this was a new and awesome experience for them Suffice it to say that Bonnie was anything but what they might have envisioned as "the colonel's wife." On one of her welcome calls, she spoke to Michelle, the wife of newly-arrived Lieutenant Rex Benedict. It turned out they had a lot in common. Three girls and a boy, and all about the same ages. Rex was older, and so the age difference between Bonnie and Michelle wasn't that great. We have kept up with the Benedicts over the years, and like the Hunleys, there need to more people like them. By the way, Rex likes to say that his young career flashed before his eyes when he learned that Michelle and Bonnie had struck up a acquaintance during that first phone call.

At Fort Campbell, there was a 101st Airborne Division coin that could be purchased at the division's museum. People in leadership positions were expected to have a coin, and have in on them at all times, as even in the shower. If you were challenged by someone presenting their coin, you were expected to produce yours in short order. If you couldn't, you owed them a beer. If you did, they bought. Good fun.

Fort Campbell also had a stable operated by Recreation Services people. You could rent a horse and ride the many backroads of the reservation. Bonnie would take the kids horseback riding and into the training area, searching for our battalion when we were in the field. She never found the 20th, but had some interesting encounters with air assault soldiers.

Good training requires resources, and good planners know it is easier to plan a year ahead than a week ahead. One of the resources that everyone seems to need is training ranges, for weapons qualification and for maneuver. So attending range conferences and getting in one's bid for training land is pretty important unless you like to practice river crossing exercises in your motor pool. At Fort Campbell with the 101st, the division's brigades had the priority for training ranges, and rightly so. But we were always at the range conferences hooking and jabbing for some training areas where we could do our combat engineer thing. Mostly we were accommodated. And linking our training to division training (see above) always helped. It also helped that the division - except for the division engineers - had little interest in the training area called the demolitions range. It is possible, within some strict but reasonable rules, to perform demolitions within the "regular" training areas, but the demo range is set up so that you can do pretty much anything you want there. To be a bit clearer: if you are performing demolitions in a "regular" training area then you have to post in advance the times and locations so that aircraft and ground troops are away from the blast zone, and the area has to have demo guards for those who might not get the word - all reasonable safety precautions. But in the demo range, everyone else except the "range owner" is not allowed there and the area is a permanent no-fly zone so you can see how things are easier to manage. Well it turned out that the demo range did have a bit of maneuver and bivouac space around it, so with some imagination we used the demo range for a variety of training. Once we had platoons build a short span of timber trestle bridge across the area, and then had another platoon come in and blow the bridge using something like four pounds or less of C-4. This made them think about the critical components that needed to be cut and also limited the damage so that another platoon could come in and be given the mission of repairing the blown bridge. Then another platoon was given the mission of blowing the bridge, et cetera. We also used commercial ammonium nitrate as cratering charges, which saved on our limited allowance of demolition materials. Good stuff.

There is a quote some place about not hassling commanders with trivial statistics. But whoever said that never participated in monthly readiness briefings to the division commander and his staff. Maintenance operational readiness rates, budget execution, numbers of Home Town News Releases submitted, indiscipline rates including AWOLs, memberships in the Association of the United States Army, Reports of Survey, accidents, you name it. After one of these sessions all the battalion commanders got a letter about the division's AUSA corporate sponsors. The letter had broken the total number of division sponsers into groups and said, "Here are your four corporate sponsors. Keep them happy. If you lose one, go get another." Well maybe not those exact words. Hmmmm. I guessed that AUSA Corporate Sponsors numbers were something that the Division Commanders must have to brief to the Corps Commander. So how was I to keep my corporate sponsors happy. Well, it turned out that we had machine gun training coming up, so we called them all and asked them to join us at the range. They all showed up, talked to soldiers, fired a few rounds, ate rations with the troops, and one declared, "I've been a corporate member for ten years now and this is the first time I've ever been invited to anything where I wasn't asked to give more money, and this is one of my best days ever." So we made it a point to invite our corporate sponsors along whenever we did something out of the ordinary. Generally, it didn't take any extra effort and all our sponsors certainly expressed their appreciation.

Another statistic that we all had to maintain was our reenlistment rate. So, our battalion, like all others, had a good NCO who was diverted from his regular duties to serve almost full time as the Battalion Reenlistment NCO. Each month he would bring me a list of those soldiers nearly the end of their enlistment and we'd work on strategies to get them to reenlist - like starting months in advance and finding the time an equipment operator was out on a project operating his equipment so he would hopefully be in a good mood. And the battalion certainly offered three-day passes and other incentives for reenlisting. Regardless, it was a lot of work and end-of-month sweat to meet our quota. . . . And one day the Army, in its wisdom, decided there would be no more reenlistment quotas. In fact, not just anyone would be eligible to reenlist. A soldier had to have a clean record, meet education standards, and be recommended. Even then, reenlistment was not guaranteed because at the point a soldier wanted to reenlist the Army might be "over" on his specialty and then reenlistment would only be possible in shortage specialties - like infantry. You know all those soldiers we were begging to re-up? Now it was the other way around. And we actually reenlisted more - and better - soldiers than ever before. Good job, Army.

Awards. A quote attributed to Napoleon is, "Men will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon." I hope that was a tongue-in-cheek comment. No one

Awards, more. Awards are not to be used as carrots on a string, as in do this and you'll get an award. But one of the statistics that could get a commander in trouble fast was the accuracy of his personnel reporting. At the time we used something called SIDPERS, the Standard Installation and Division Personnel System. And in 1981-84 we were at the infancy of technology, so there were cards to be punched and the whole process was difficult and took a whole lot of diligence on the part of the S1 clerks who made the entries. The standard was 96% or better accuracy rate. Drop below that for a month or so and your unit got lots of attention, and not of the good kind. So shortly after I arrived I got my SIDPERS accuracy report and it was below 96%. I pulled a yellow OF 41, ROUTING AND TRANSMITTAL SLIP, off its pad and wrote a note to the S1 in my purple pen. The form, called a Buck Slip, said SIDPERS ≥ 96% for 3 straight Mos = AAM. No, that is NOT the way an awards system is supposed to be run. But we never ever had a SIDPERS problem for the rest of my three years.

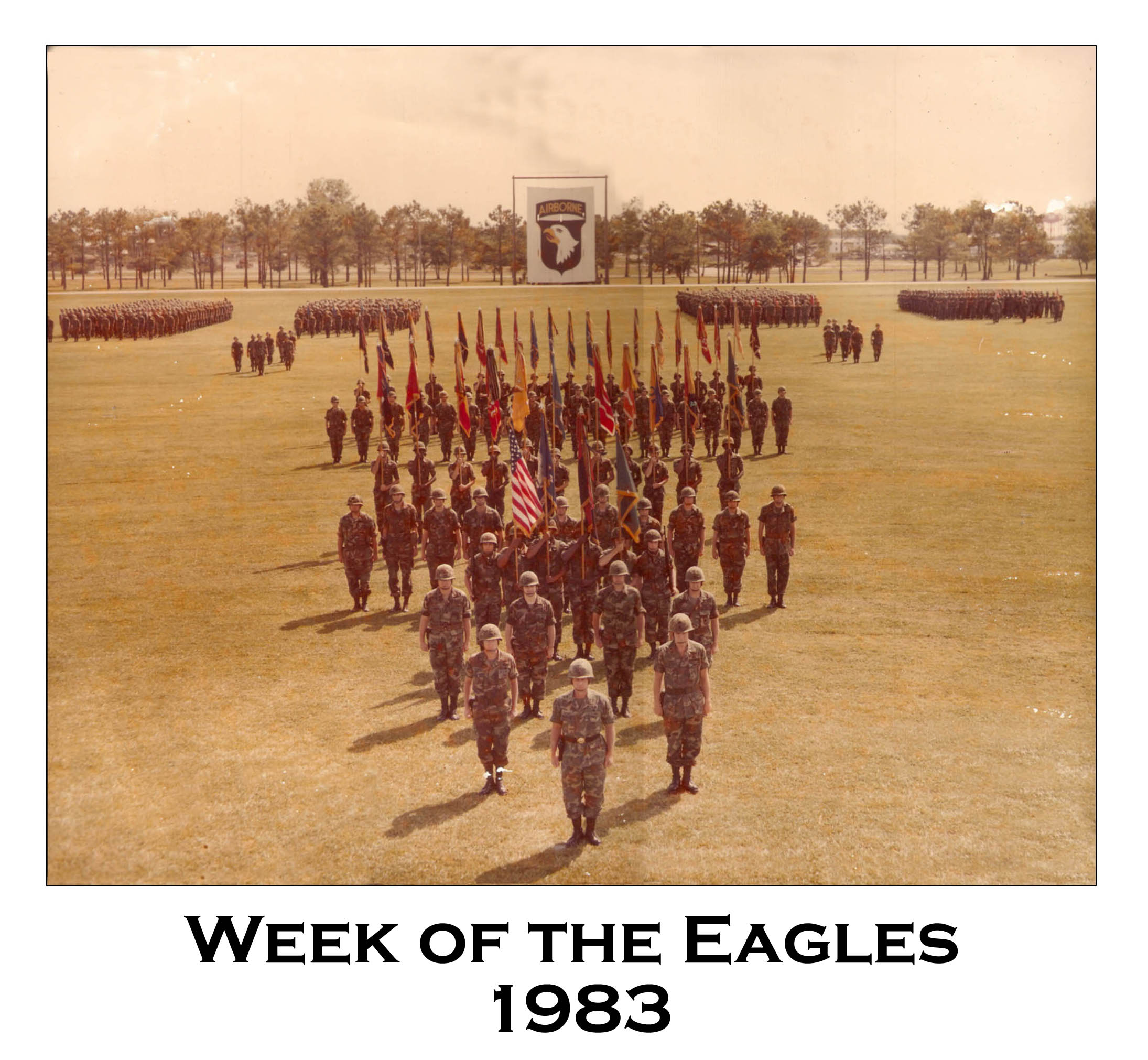

Each year Fort Campbell had its Week of the Eagles, a time of various competitions among battalions, culminating with the Division Review. We didn't figure it out right away, but we had a few chances to get it right. For example, there was a cake baking competition for the cooks.

Each year we had an Engineer Ball. For the years I was with the 20th, we made all of the arrangements for this event, and invited our fellow engineer battalion, the 326th.

The 20th Engineer Battalion was selected to participate in REFORGER in Europe, a major exercise. People reading this may not know of REFORGER, but Exercise REFORGER (REturn of FORces to GERmany) was an annual exercise conducted during the Cold War by NATO. The exercise was intended to ensure that NATO had the ability to quickly deploy forces to Germany in the event of a conflict with the Soviet Union. The first exercise was conducted in 1967, at a time when some forces were withdrawn back to the U.S. mainland, and continued annually past the end of the Cold War. The 20th Engineer Battalion was a REFORGER unit. This meant that the 20th was earmarked for an early arrival in Europe to bolster US forces there in the event of a conflict. So, you ask, how does an engineer battalion with all its trucks, engineer equipment, tools, tents, sets, kits, and outfits get to Germany fast? The answer is that REFORGER units had complete sets of equipment prepositioned in Germany

I served a full three years with the battalion, something that doesn't happen today, and regard my time with the Build and Fight battalion with very fond memories.

My time with the 20th also generated some other good stories, and they can be found here. Seriously, these are, in my opinin really good stories that you will enjoy, such as:

The 20th Engineer Battalion was a non-divisional combat engineer battalion assigned to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, home of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Organizationally, it was assigned to the Eagle Support Brigade, a collection of other non-divisional units assigned to Fort Campbell. For almost all of my time with the 20th Engineers the Eagle Support Brigade was commanded by Colonel Jere H. Akin who went on to retire as a major general and be a member of the Quartermaster Hall of Fame (2003).

The 20th Engineer Battalion was a non-divisional combat engineer battalion assigned to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, home of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Organizationally, it was assigned to the Eagle Support Brigade, a collection of other non-divisional units assigned to Fort Campbell. For almost all of my time with the 20th Engineers the Eagle Support Brigade was commanded by Colonel Jere H. Akin who went on to retire as a major general and be a member of the Quartermaster Hall of Fame (2003).

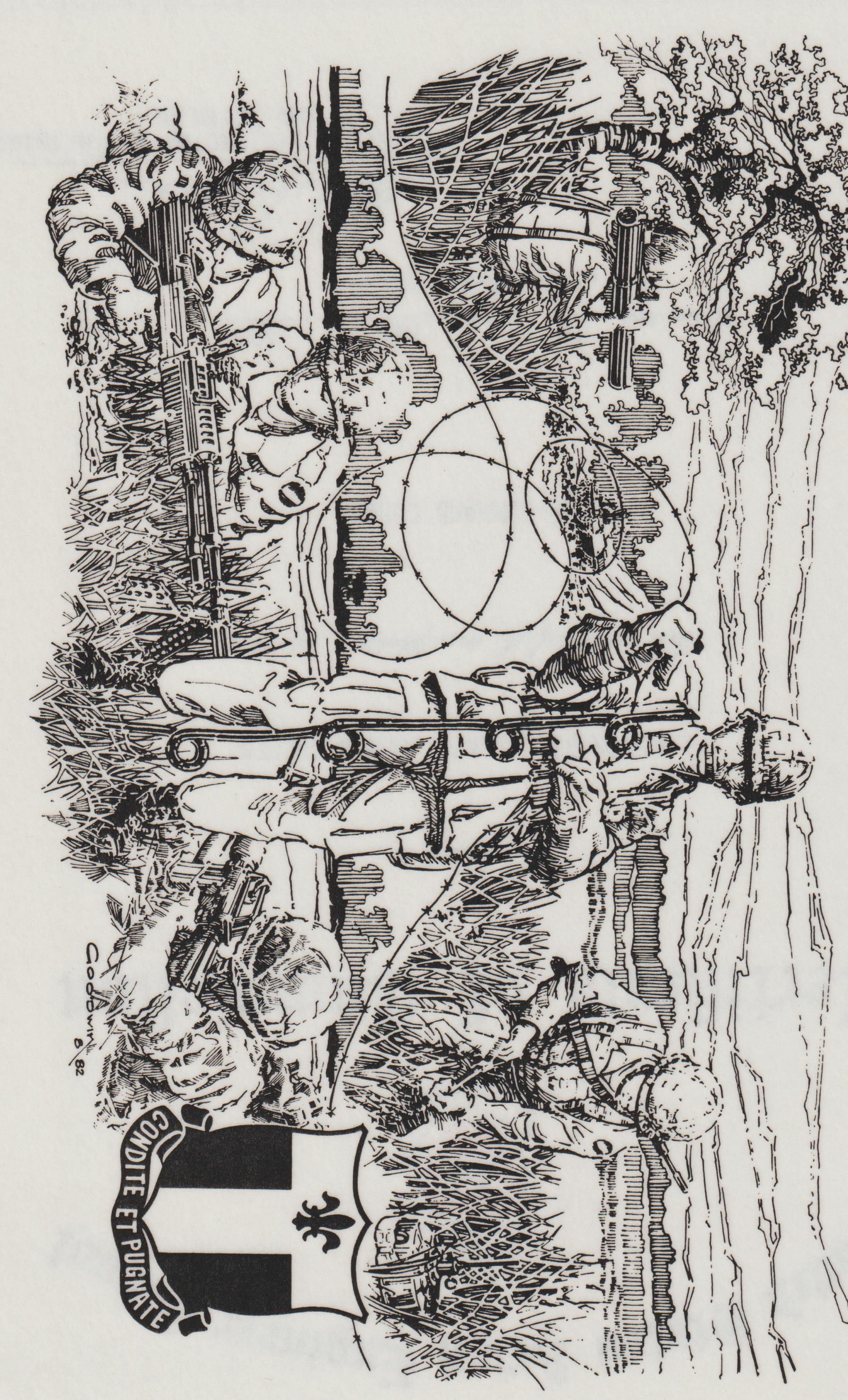

the effect was that the brigade would go out with two engineer companies supporting it. The brigades were fine with this, as were the divisional engineers. There was one difference, however. Our companies took their field time with the 101st very seriously, and worked hard to generate scenarios of interest and value to themselves and to the infantry of the 101st. For example, our engineers might go out and build a defensive complex of bunkers protected by barbed wire and then exercise with the infantry to use bangalore torpedoes to blow the wire and let the infantry assault and blow the bunkers. And on a major brigade vs brigade training exercise, elements of the bridage that one of our companies was supporting were more-than-pleasantly surprised to find that when they withdrew to to the next ridgeline back, our engineers had already prepared their defensive position. Yes, the brigades came to like us a lot.

the effect was that the brigade would go out with two engineer companies supporting it. The brigades were fine with this, as were the divisional engineers. There was one difference, however. Our companies took their field time with the 101st very seriously, and worked hard to generate scenarios of interest and value to themselves and to the infantry of the 101st. For example, our engineers might go out and build a defensive complex of bunkers protected by barbed wire and then exercise with the infantry to use bangalore torpedoes to blow the wire and let the infantry assault and blow the bunkers. And on a major brigade vs brigade training exercise, elements of the bridage that one of our companies was supporting were more-than-pleasantly surprised to find that when they withdrew to to the next ridgeline back, our engineers had already prepared their defensive position. Yes, the brigades came to like us a lot.

(Later, in Europe, I learned that similar engineer battalions there had nearly $1M to maintain the same equipment.) Also, each company's maintenance operation was supervised by a staff sergeant (E-6). Again I complained to FORSCOM and again help was provided as the maintenance supervisor was upgraded to Sergeant First Class (E-7). (Later, I would find that units in Europe would have an E-7 AND a warrant officer in each company.) One of the things I did to promote maintenance was with new lieutenants to the battalion. Shortly after their arrival we would have a normal "Meet and Greet" in my office when we would learn a little bit about each other and where I would talk about the battalion's history and some of my more important policies. Then, before the office call was over, I would schedule a time about 60 days out where the new lieutenant and I would meet in the motor pool. Now I greatly admire infantry soldiers. They bear the brunt of any fighting and shed their blood, if necessary, to accomplish their missions. At Fort Campbell, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) is structured to be able to rapidly respond to military situations around the world so every platoon leader in this division has huge responsibilities, to include commanding men who may have to perform while in harm’s way, a task requiring the utmost leadership. An engineer platoon leader in a corps level combat engineer battalion also has important responsibilities and is required to demonstrate leadership. But the structure of his organization is not necessarily designed for worldwide appointment on short notice. It is designed to support early deploying (light) units with equipment that is bigger and stronger. Therefore our lieutenants’ responsibilities included ensuring that the many individual and crew served weapons, sets, kits, outfits, generators, radios, mine detectors, trucks, and trailers that come with a combat engineer platoon are all properly maintained. So back to my scheduled 60-day-out session with my new lieutenant. At that time the lieutenant was to have everything he "owned" out for inspection, and he was to be ready to talk about its maintenance and operation. Lieutenants worked hard not to be embarrassed during these sessions, and the word among lieutenants was that they weren't really introduced to the battalion until they had their session with "the colonel" in the motor pool. Yes, there were a few lieutenants who got embarrassed, but I doubt there were any lieutenants in the Army with a better knowledge of their equipment as a result of this exercise. One of my regrets was not inviting Colonel Akin or BG Bethke down to one of those inspections - they each would have had a great deal more respect for how much equipment, vehicles, sets, kits, and outfits each engineer lieutenant was responsible for.

(Later, in Europe, I learned that similar engineer battalions there had nearly $1M to maintain the same equipment.) Also, each company's maintenance operation was supervised by a staff sergeant (E-6). Again I complained to FORSCOM and again help was provided as the maintenance supervisor was upgraded to Sergeant First Class (E-7). (Later, I would find that units in Europe would have an E-7 AND a warrant officer in each company.) One of the things I did to promote maintenance was with new lieutenants to the battalion. Shortly after their arrival we would have a normal "Meet and Greet" in my office when we would learn a little bit about each other and where I would talk about the battalion's history and some of my more important policies. Then, before the office call was over, I would schedule a time about 60 days out where the new lieutenant and I would meet in the motor pool. Now I greatly admire infantry soldiers. They bear the brunt of any fighting and shed their blood, if necessary, to accomplish their missions. At Fort Campbell, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) is structured to be able to rapidly respond to military situations around the world so every platoon leader in this division has huge responsibilities, to include commanding men who may have to perform while in harm’s way, a task requiring the utmost leadership. An engineer platoon leader in a corps level combat engineer battalion also has important responsibilities and is required to demonstrate leadership. But the structure of his organization is not necessarily designed for worldwide appointment on short notice. It is designed to support early deploying (light) units with equipment that is bigger and stronger. Therefore our lieutenants’ responsibilities included ensuring that the many individual and crew served weapons, sets, kits, outfits, generators, radios, mine detectors, trucks, and trailers that come with a combat engineer platoon are all properly maintained. So back to my scheduled 60-day-out session with my new lieutenant. At that time the lieutenant was to have everything he "owned" out for inspection, and he was to be ready to talk about its maintenance and operation. Lieutenants worked hard not to be embarrassed during these sessions, and the word among lieutenants was that they weren't really introduced to the battalion until they had their session with "the colonel" in the motor pool. Yes, there were a few lieutenants who got embarrassed, but I doubt there were any lieutenants in the Army with a better knowledge of their equipment as a result of this exercise. One of my regrets was not inviting Colonel Akin or BG Bethke down to one of those inspections - they each would have had a great deal more respect for how much equipment, vehicles, sets, kits, and outfits each engineer lieutenant was responsible for.

. . . but they never asked.

Well, this is maintenance-related. The battalion had parking spots out in front of its headquarters, and one of these was for the battalion commander. That is where, from June 1981 through June 1984, I parked our 1974 Ford "Polly" Pinto, who was showing her age. Somehow, next to the battalion commander's spot was a space marked SDO for Staff Duty Officer. The SDO, almost always a lieutenant, would report for duty somewhere around 1700. So since I usually left later than that, there would be a time when the lieutenant's personal vehicle would be parked next to poor old Polly. Of course, all the lieutenants drove brand new cars, so there would often be the 1982 Corvette parked next to the 1974 Ford. That didn't bother me a bit, and the rumor - that I would go to the motor pool to rip up that lieutenant if his Army vehicles were not being maintained just as well as he maintained his personal vehicle - is just not true.

wants a soldier who does things for recognition; we want soldiers who do things out of loyalty, pride, fortitude and the other attributes of professionalism. But the Army does have peacetime awards for service and achievement and most soldiers, while not bragging about their medals and ribbons, wear them proudly. I had a liberal awards policy throughout my career. Or was it so liberal? I would talk to the NCOs of the battalion and ask, "Who here left an assignment where you know in your heart that you did an excellent job, far above what was called for, and got no recognition?" Invariably about 100% of hands would go up. So I'd say, "Then how about you taking care of your soldiers in this battalion so one day they don't have to raise their hand like you just did?" A battalion commander

wants a soldier who does things for recognition; we want soldiers who do things out of loyalty, pride, fortitude and the other attributes of professionalism. But the Army does have peacetime awards for service and achievement and most soldiers, while not bragging about their medals and ribbons, wear them proudly. I had a liberal awards policy throughout my career. Or was it so liberal? I would talk to the NCOs of the battalion and ask, "Who here left an assignment where you know in your heart that you did an excellent job, far above what was called for, and got no recognition?" Invariably about 100% of hands would go up. So I'd say, "Then how about you taking care of your soldiers in this battalion so one day they don't have to raise their hand like you just did?" A battalion commander  had the authotity to award the Army Achievement Medal, and we awarded a lot. Or did we? At the monthly awards ceremony I would typically present about 20 AAMs for various reasons. But for a 600 man battalion that 20 is about the number of soldiers who would rotate out of the battalion each month, so I felt we were about half of where we needed to be. I felt that a good soldier who worked hard, stayed out of trouble, and was well thought of by his sergeants should have the opportunity to earn two AAMs for achievement during his time in the battalion. Very, very good soldiers should also be put in for the Army Commendation Medal for service (approved at the brigade level).

had the authotity to award the Army Achievement Medal, and we awarded a lot. Or did we? At the monthly awards ceremony I would typically present about 20 AAMs for various reasons. But for a 600 man battalion that 20 is about the number of soldiers who would rotate out of the battalion each month, so I felt we were about half of where we needed to be. I felt that a good soldier who worked hard, stayed out of trouble, and was well thought of by his sergeants should have the opportunity to earn two AAMs for achievement during his time in the battalion. Very, very good soldiers should also be put in for the Army Commendation Medal for service (approved at the brigade level).

Okay, let's ask the question, how should the cake be decorated? We got a lot of good answers from our cooks, but the right answer is, "...with a great big Screaming Eagle on it." Oh, yes, we won the cake baking. And then there was MOS testing. The first thing was to make it worthwhile for soldiers to train up for the event, and this was done with the enticements of passes and other things under my control. The second thing was to recognize that only two soldiers per MOS could win, so even though we had LOTS of MOS 12B (Combat Engineer) soldiers, the trick was to make sure soldiers from a variety of specialties were in the competition: welders, clerks, equipment operators ... as well as our combat engineers. The third thing was to recognize that we could - in two weeks of preparation - greatly increase a soldier's knowledge in the skills of the competition, but that we could not in this time increase a PT score from 190 to 250. So our primary qualifying event was the PT Test. Then we went to work training up our high scorers. Did we clean house on the skills competition? You bet. For the Division Review, we had a couple of practices. I told the soldiers that once we were positioned on the Parade Field and standing there in the Parade Rest position, there would be parachutists jumping in and and an air assualt demonstration as the ceremony started. I said for the practice I wanted them to go ahead and look up and watch the overhead parachutists and air assault demonstration. I pointed out that when they all had their good look, I would be severely chewed out for having a battalion of bobbing head troops, but this was becauseon the real day I expected them all standing steady and not looking, even if something landed on them. I also reminded them that anyone out drinking the night before and who fainted while standing in formation would be stepped on by everyone else because I was ordering our medics not to pick anyone up. Well, something must have worked, because that year we won the Division Review marching contest. Not too shabby because there were more than 20 battalion-size units in the parade. [Note on the photo: In the front was Major General Bagnal, the Division Commander. Behind him are his two Assistant Division Commanders. Behind them are the G1, G2. G3, and G4 Staff Officers. Then the Division Color Guard. Behind them are the Brigade Commanders and behind them are the brigade flags. And behind them are the Battalion Commanders. Lieutenant Coloonel Braden is fourth from right and one can identify Braden because of the bowed legs. Click on the picture to enlarge it.]

Okay, let's ask the question, how should the cake be decorated? We got a lot of good answers from our cooks, but the right answer is, "...with a great big Screaming Eagle on it." Oh, yes, we won the cake baking. And then there was MOS testing. The first thing was to make it worthwhile for soldiers to train up for the event, and this was done with the enticements of passes and other things under my control. The second thing was to recognize that only two soldiers per MOS could win, so even though we had LOTS of MOS 12B (Combat Engineer) soldiers, the trick was to make sure soldiers from a variety of specialties were in the competition: welders, clerks, equipment operators ... as well as our combat engineers. The third thing was to recognize that we could - in two weeks of preparation - greatly increase a soldier's knowledge in the skills of the competition, but that we could not in this time increase a PT score from 190 to 250. So our primary qualifying event was the PT Test. Then we went to work training up our high scorers. Did we clean house on the skills competition? You bet. For the Division Review, we had a couple of practices. I told the soldiers that once we were positioned on the Parade Field and standing there in the Parade Rest position, there would be parachutists jumping in and and an air assualt demonstration as the ceremony started. I said for the practice I wanted them to go ahead and look up and watch the overhead parachutists and air assault demonstration. I pointed out that when they all had their good look, I would be severely chewed out for having a battalion of bobbing head troops, but this was becauseon the real day I expected them all standing steady and not looking, even if something landed on them. I also reminded them that anyone out drinking the night before and who fainted while standing in formation would be stepped on by everyone else because I was ordering our medics not to pick anyone up. Well, something must have worked, because that year we won the Division Review marching contest. Not too shabby because there were more than 20 battalion-size units in the parade. [Note on the photo: In the front was Major General Bagnal, the Division Commander. Behind him are his two Assistant Division Commanders. Behind them are the G1, G2. G3, and G4 Staff Officers. Then the Division Color Guard. Behind them are the Brigade Commanders and behind them are the brigade flags. And behind them are the Battalion Commanders. Lieutenant Coloonel Braden is fourth from right and one can identify Braden because of the bowed legs. Click on the picture to enlarge it.]

One of the nice things we did was to make table settings that included wooden engineer castles, and inside each of the three turrets was a candle. This was fortunate because at the first Engineer Ball the power went out, and for a long time the only light we had was from the candles from our table settings, which worked well under the circumstances . (As a note, in the next Engineer Ball, I made arrangements with CW3 Hunley to have a contact truck standing by in case the power went out again. And wouldn't you know it, the power did go out, but we were ready.) One of the really, really fun parts of the Engineer Ball that I remember, was our engineer skit. There is a song, which can be readily found on the Internet, that is sometimes called the Engineer Drinking Song or the Engineer Hymn Or the Engineer Battle Song. Here is the chorus:

We are, we are, we are, we are, we are the Engineers

It has many, many verses. What we did was erect a cloth screen behind the singers that had a couple of tables behind it. On these tables were laid the various costumes and gear necessary to act out the next verse. For example, one of the verses was:

We can, we can, we can, we can, demolish forty beers

Drink rum, drink rum, drink rum all day, and come along with us

'Cause we don't give a damn for any old man who don't give a damn for us!

Godiva was a lady who through Coventry did ride.

Let's say that Company B had responsibility for this verse. That meant that when the other battalion officers were singing the chorus leading up to this verse, the Company B officers would disengage themselves from the main body of singers, quickly move behind the curtain, put on wigs and costumes and gather up any other gear, and run back out in front of the body of singers to act out - in this case - the Lady Godiva verses. To say it was hilarious is an understatement.

Showing all the villagers her lovely lilly hide.

The most observant fellow was a Engineer of course,

He's the only one that noticed that Godiva rode a horse! so that all REFORGER units had to do was fly there and draw their equipment out of storage. One of the objectives of each REFORGER exercise was, then, to test the drawing of the equipment. But now let's step away from the history lesson. The support we received from MG Bagnal and the post in preparation for this exercise was absolutely fantastic. Our line companies rotated to Fort Leonard Wood for refresher training conducted by US Army Engineer School cadre. The battalion also went to Wisconsin and drew equipment from a Reserve component holding area, something it would do once it arrived in Germany. The Division Commander of the 101st turned his Training Support Center loose to provide us with a foot locker full of mementos that we could give to local officials as presents. A REFORGER exercise lasts two weeks. But due to deployment considerations, we arrived two weeks early for the actual exercise. It was a bit hard operating in the field two weeks before the exercise started, because all the units that were to support us were either still in route to Germany or still in their German garrison. But we managed. The pig farm worked great. We also did well during the exercise. It got so that putting up a tent late at night, packing it away the morning, and shaving with cold water out of a helmet was just daily business. One of my lasting memories of the exercise came when the Assistant Division Commander, BG Bethke, came to visit. We were out very late at night checking on various units of the battalion when down the road comes a five ton dump truck, the battalion's squad vehicle for its combat engineers. Guess what? The air guard was out and alert, as were the soldiers in the vehicle - not bad for being at it for many weeks. Yes, I was proud of them. After the exercise we assembled at a staging area awaiting our flight back home. This wait was another two weeks. One good thing about going into the post-exercise phase, was that drinking was now allowed, and the beer tent in the assembly area was extremely popular. To keep soldiers occupied, bus trips were arranged to many of the nearby scenic sites. As a matter of control, I said that any company with an incident at night would not be allowed to leave the camp the next day. I went on one of these trips, to Rothenburg, a truly outstanding town for site seeing. I watched some of the soldiers who were on that trip; they got off the bus at the town center; walked over to the nearest gasthaus; and sat out front drinking German beer until it was time to re-load the bus and depart. I wonder if they even remembered the name of the town, but they did have a good time. As the number of units drew down in the post-exercise area, our troops became emboldened in the beer tent, and anyone could easily hear them singing the 101st Airborne Fight Song each night. We returned to Fort Campbell as a close knit organization with many good shared experiences.

so that all REFORGER units had to do was fly there and draw their equipment out of storage. One of the objectives of each REFORGER exercise was, then, to test the drawing of the equipment. But now let's step away from the history lesson. The support we received from MG Bagnal and the post in preparation for this exercise was absolutely fantastic. Our line companies rotated to Fort Leonard Wood for refresher training conducted by US Army Engineer School cadre. The battalion also went to Wisconsin and drew equipment from a Reserve component holding area, something it would do once it arrived in Germany. The Division Commander of the 101st turned his Training Support Center loose to provide us with a foot locker full of mementos that we could give to local officials as presents. A REFORGER exercise lasts two weeks. But due to deployment considerations, we arrived two weeks early for the actual exercise. It was a bit hard operating in the field two weeks before the exercise started, because all the units that were to support us were either still in route to Germany or still in their German garrison. But we managed. The pig farm worked great. We also did well during the exercise. It got so that putting up a tent late at night, packing it away the morning, and shaving with cold water out of a helmet was just daily business. One of my lasting memories of the exercise came when the Assistant Division Commander, BG Bethke, came to visit. We were out very late at night checking on various units of the battalion when down the road comes a five ton dump truck, the battalion's squad vehicle for its combat engineers. Guess what? The air guard was out and alert, as were the soldiers in the vehicle - not bad for being at it for many weeks. Yes, I was proud of them. After the exercise we assembled at a staging area awaiting our flight back home. This wait was another two weeks. One good thing about going into the post-exercise phase, was that drinking was now allowed, and the beer tent in the assembly area was extremely popular. To keep soldiers occupied, bus trips were arranged to many of the nearby scenic sites. As a matter of control, I said that any company with an incident at night would not be allowed to leave the camp the next day. I went on one of these trips, to Rothenburg, a truly outstanding town for site seeing. I watched some of the soldiers who were on that trip; they got off the bus at the town center; walked over to the nearest gasthaus; and sat out front drinking German beer until it was time to re-load the bus and depart. I wonder if they even remembered the name of the town, but they did have a good time. As the number of units drew down in the post-exercise area, our troops became emboldened in the beer tent, and anyone could easily hear them singing the 101st Airborne Fight Song each night. We returned to Fort Campbell as a close knit organization with many good shared experiences.