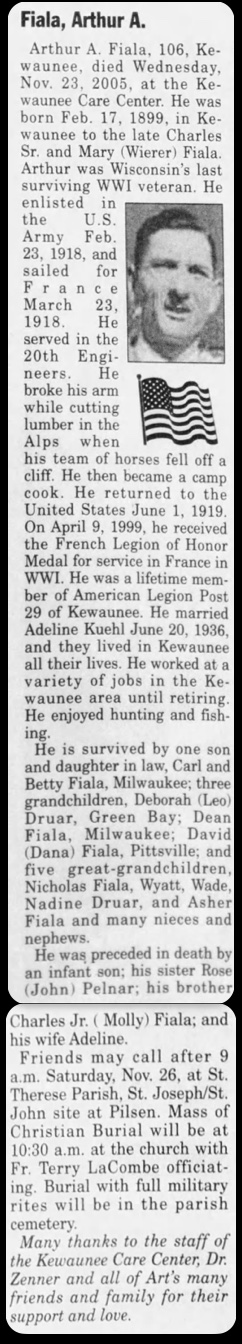

1899 - 2005

Company B, 9th Battalion (26th Company), 20th Engineer Regiment

The Last Surviving Soldier of the 20th Engineers from WW1

Excerpts from Interviews with Art Fiala in 2003 and 2005, from The Last of the Doughboys, by Richard Rubin

He told me he went to a recruitment center in Green Bay; they must have

sent him to Columbus Barracks, Ohio, because that's where his discharge

papers say he officially enlisted, on February 23, 1918. "Now, hear," he

said. "When I enlisted, I didn't tell the recruiter what branch of service I

wanted to get into. I said, 'That's up to you.' I said, 'Get me into an outfit

that goes over to France quick.' And he put me into an engineer outfit, the

20th Engineers. And we had two weeks' training . . . that was it."

He told me he went to a recruitment center in Green Bay; they must have

sent him to Columbus Barracks, Ohio, because that's where his discharge

papers say he officially enlisted, on February 23, 1918. "Now, hear," he

said. "When I enlisted, I didn't tell the recruiter what branch of service I

wanted to get into. I said, 'That's up to you.' I said, 'Get me into an outfit

that goes over to France quick.' And he put me into an engineer outfit, the

20th Engineers. And we had two weeks' training . . . that was it."

Somewhere in all that rush, the 9th Battalion of the 20th Engineers may

have had an experience that, in America at least, was fairly singular to

World War I. It was the last week of March, 1918. "We were supposed to go

to New York to get on the boat," Private Fiala recalled eighty-five years

later. "We had two boxcars full of barracks bags, with all the equipment that

we were supposed to have when we got to our destination in France." He

paused, then pounced: "It caught fire. And we think, I think it was

sabotaged," he explained. "So

when we got on the boat," he told me, "all we had was a pack, our pack

sack with a couple blankets and a mess kit. That's all we had." That, and the

clothes on their bodies.

Somewhere in all that rush, the 9th Battalion of the 20th Engineers may

have had an experience that, in America at least, was fairly singular to

World War I. It was the last week of March, 1918. "We were supposed to go

to New York to get on the boat," Private Fiala recalled eighty-five years

later. "We had two boxcars full of barracks bags, with all the equipment that

we were supposed to have when we got to our destination in France." He

paused, then pounced: "It caught fire. And we think, I think it was

sabotaged," he explained. "So

when we got on the boat," he told me, "all we had was a pack, our pack

sack with a couple blankets and a mess kit. That's all we had." That, and the

clothes on their bodies.

"There were eleven boats in our convoy. The first four days out on the ocean were beautiful. I enjoyed the ride. Then I got seasick. I was sick for four days. And in the meantime, they wouldn't let us take our clothes off, so in case we got torpedoed, we had our clothes on. Well, and I was seasick for four days, and I decided to try to get something to eat. And I went down, I got in the galley, and I got half of a grapefruit. And I ate that, and then I was going to get another one, and then the abandon-ship alarm sounded. We had to all go up on deck. They thought we were going to be hit. Well, it so happened there wasn't any, uh . . ." "U-boats?" "U-boats, that's it. What came to meet us was subchasers. Oh, are they beautiful! . . . They're narrow and slick, and boy can they travel! They were, see there were eleven boats in our convoy, and they were, they were just running between our boats."

"When we landed, they marched us uphill about three miles," Private Fiala recalled. "So they said plunk these [packs] in the barracks. But we got up there, there was no barracks. There was nothing but a field with pup tents. And it was pouring, it was all mud. We couldn't sleep. Well, good thing, we were called out to go back down to the boat. And we worked there, we unloaded boats all night. We were pooped out. Then they took us back up this hill. And then the next day we were loaded on a train. Looked like boxcars. No seats in there, just lay down like a dog. And I don't know, over two or three days we were on, across France. Slow train!" Boxcars in France back then were labeled "40-8"...that is, forty men per car, or eight horses.

See the YouTube video of a portion of the interview with Arthur Fiala

"Then," he told me, "we landed in a little town called La Cluse. And that was in the foothills of the Alps mountains. Here, I've got to tell you one thing about that: See, when we got there, we found out that our carload of food was lost. We were hungry, hungry as hell! So I thought, I'll take a walk uptown, and maybe I could buy something. I didn't have much money, but I found some figs." It was the first break he seemed to catch in a while. He even got a chance to laugh. "There was a Frenchman walking ahead of me," he said, "and he stopped by a big tree to take a pee. And while he was taking a pee, there was a woman coming down the street, and he was holding it in one hand and tipping his hat with the other hand. That was the first thing that struck me as funny."

Later that day, the cook managed to find some beans. "Boy, that tasted like ice cream, I'll tell you. That was good. Piece of bread and some of those beans."

The men marched another three miles up to a plateau, where they pitched camp by a creek. "And we didn't have our clothes off for nine days; we pulled off our clothes and jumped in the creek to wash off. And then a lot of the boys started fires around and everything." It was, after all, still cold up there. That night, they pitched tents and slept; in the morning, they awoke to snow. "Snow, snow, snow, everywhere . . .we had no extra stockings, no nothing. Well, it snowed so damn hard we couldn't, we didn't know where to sleep. And there was a farmer up there, he let us sleep in the barn. So we all--can you picture two hundred and fifty guys sleeping in a barn. Like sardines!"

Eventually, someone tracked down that boxcar full of food, but trucks couldn't make it up to camp in the snow, so 250 men had to trudge down the mountain and carry it back up by hand. Dinner that night was beef stew. "They gradually got a kitchen going and everything. And do you know what we were up there for? We were up there logging. We were making products, wood products, to be shipped to the front."

"Well, logs, railroad ties, camouflage poles, all kinds of stuff like that . . . There was about half of them guys in that outfit that were real lumberjacks. And we younger guys, we would go up in the woods, up in the woods in the mountains, and they would cut the logs down, and then we younger guys would chop the limbs off. They called us, we were 'swampers' . . . Well, anyway, then, here's the part: One day we were going down the mountain with a team of horses, there was about seven of us on the wagon, and the horses got wild and they jumped, they went off the side of the mountain. And we all went down the mountain. And lucky thing there was enough trees there to stop us. But anyway, I got, we all got hurt. I broke my wrist . . . so I didn't, I couldn't do anything for a while. And when my wrist got better, they gave me a job, to work around the kitchen."

"In the beginning, when we were there, they used to cut logs up in the mountains," Art Fiala explained to me. "And they would slide them down the mountain, and they would peel them, you know, so they were slippery. And a personal friend of mine, he got killed from a log, yeah, knocked him down. We had about eight guys I think got killed, died in the outfit . . . And one guy," he declared, "one guy was murdered. Somebody, we found one of our men under a bridge with a hole in his head. Somebody hit him."

Some of the men in his outfit were felled not by logs, but by disease, which, despite great medical advances since the last big war, still killed thousands of Americans in uniform during World War I. It even, almost, managed to kill Art Fiala.

It started in the kitchen. "For some reason or other," he recalled, "the ventilation was bad in that camp, and I got pleurisy." Pleurisy: an inflammation of the pleura, which line the lungs. Often caused by infection. It can make breathing very painful. It can also kill you any number of unpleasant ways. It's one of those diseases you don't hear about anymore; today it can be cured by a visit to a doctor's office and some over-thecounter drugs. Not then, though.

"I was sick," he told me, nodding gravely over the din caused by the machine that was pumping oxygen into his nose. "And I called the doctor. He came down, he looked at me, just put his head in the tent. He never touched me. He left a couple of aspirin tablets. That's all I got." He was sitting up now, looking disgusted, but lively.

"Well, here's the point," he continued. "On the edge of town, there was a woman living. She had about three little kids. She was taking care of a railroad crossing, I don't know what she had to do. She found out I was sick, she come to the tent, she brought hot tea to me. That woman never failed," he said emphatically. "Until I got well, she came in three times a day. And one day, one day she came with a plaster, plastered my chest even." His hands mimicked the act across his chest. "She was good."

"I'll never forget, never forget her," her grandfather asserted. "I give her a lot of credit. And here's the point: One day, one day I heard we were going to break up that camp. So at ten o'clock at night, when everybody was supposed to be in bed, I went to my kitchen. I took a flour sack; we used to get those tins of bacon, like that, like the big tin. I took, I gave her a can of that bacon, I gave her flour, sugar, coffee, all I could carry on my back. And I brought it to her that night. I woke them up at ten o'clock at night. Oh," he said, nodding his head earnestly, "you've never seen any happier people. They deserved it." Staples--not to mention luxuries like bacon--were scarce for civilians in France.

"One day, a couple of the boys, we decided we were going to take a trip, a trip uptown," he told me. "And maybe have a little fun for a change, see? And I didn't get back to camp to make supper. And when I got back up . . . my kitchen was all ripped to hell. They were, guys were hungry and broke in the kitchen and opened up all kinds of cans and all kinds of stuff. And the sergeant that was in charge of the camp, he come up to me and he says, 'You're fired!' On account of what I did, see.

"Well, the next day," he continued, "a motorcycle with a sidecar came down and picked me up and took me back to camp. I thought, 'Oh, boy, now I'm in for it. I'm going to get hell!' But when I got back to camp, I was greeted with open arms! And all the officers come up to me and said: 'You're promoted to officer's cook!'" He smiled.

Art Fiala spent the rest of the war as a cook--at La Cluse, and Nantua, and in la Foret de Meyriat. Though he, and the rest of the 20th Engineers, were behind the lines, the war managed to reach them anyway, this way or that. "One thing I never forgot," he told me, "in one camp, one of them camps where I was cooking, we got some casualties came there. And one guy come up to me and asked me if I could give him a job in the kitchen. And I said, 'Yes, I'll give you a job in the kitchen.' He was the principal from a high school."

All in all--unless you counted that broken wrist, that bout with pleurisy, and those long, soggy, exhausting first weeks in France--it sounded to me like Art Fiala had had a pretty good time Over There. He enjoyed the work (especially making pancakes), was well liked, well treated by his officers, and well fed. After the armistice, he was transferred to a camp in Bordeaux, where he only had to cook every third day. He scaled fences and hopped trains for free with his buddies, was once sent down to the Spanish border in a car to deliver food to some big shot, and enjoyed the company of French women more than he cared to discuss with me in detail, at least with his granddaughter around. "My wife used to throw that up to me all the time," he said with a hint of mock exasperation.

"I got a card from a girl from France," he explained to me. "She said, 'We're all thinking about you, we all like you,' or something like that.

"So tell me about meeting the girls over there," I said to him. "What was that like?"

"They were, they were pretty nice," he said with a big smile.

"Where did you meet them?"

"I don't know."

"I don't remember too much about that. But I remember, I remember I used to have one girlfriend I know of.

"Would you go into town?"

"Oh, hey, listen," he said, earnestly. "They were looking for Americans. Oh, hell!"

"Why was that?"

"I don't know. They wanted us. They liked us. They liked American boys."

"Were they pretty?"

"Oh, yeah." He nodded. "Some of them were pretty nice."

"What would you do?" I asked. "Would you go dancing?"

"No, just walk around ... I don't know," he said.

He made his way back to the Midwest, worked for a bit at a candy factory in Chicago (he was on an assembly line where peanuts were coated with chocolate), ran a taxi service in Kewaunee for a while, spent four years in northern Wisconsin just hunting and fishing, living for free at some rich man's lodge. He was a foreman at the Kewaunee Brewery for a while during Prohibition; it made liquid wort in those years.

He told me that in 1920, he bought an old car and turned it into the world's first camper, so that he and his brother could take it hunting. Sold it four years later to a circus. He brewed chokecherry wine, showed me the recipe; it was written on a piece of Fiala's Taxi Service stationery. He dated his wife for eight years, married her at age thirty-seven. Eventually, they owned a onehundred- acre farm; he told me farming was the best thing he ever did.

They

had one child, a son, Carl. They called him Carlie. Private Fiala said he'd

been in the American Legion for so long that they paid his dues for him

now; that the secret to his longevity was that he ate peanuts every day.

He passed away seven months later, just before Thanksgiving. He died

where he'd been born, where he'd lived for just about every one of his 106

years, not far from every place he'd ever spent any considerable stretch of

time. Except one, of course. Were it not for the Great War, he almost

certainly would have never traveled to a place so distant, and strange, as

France was to him.